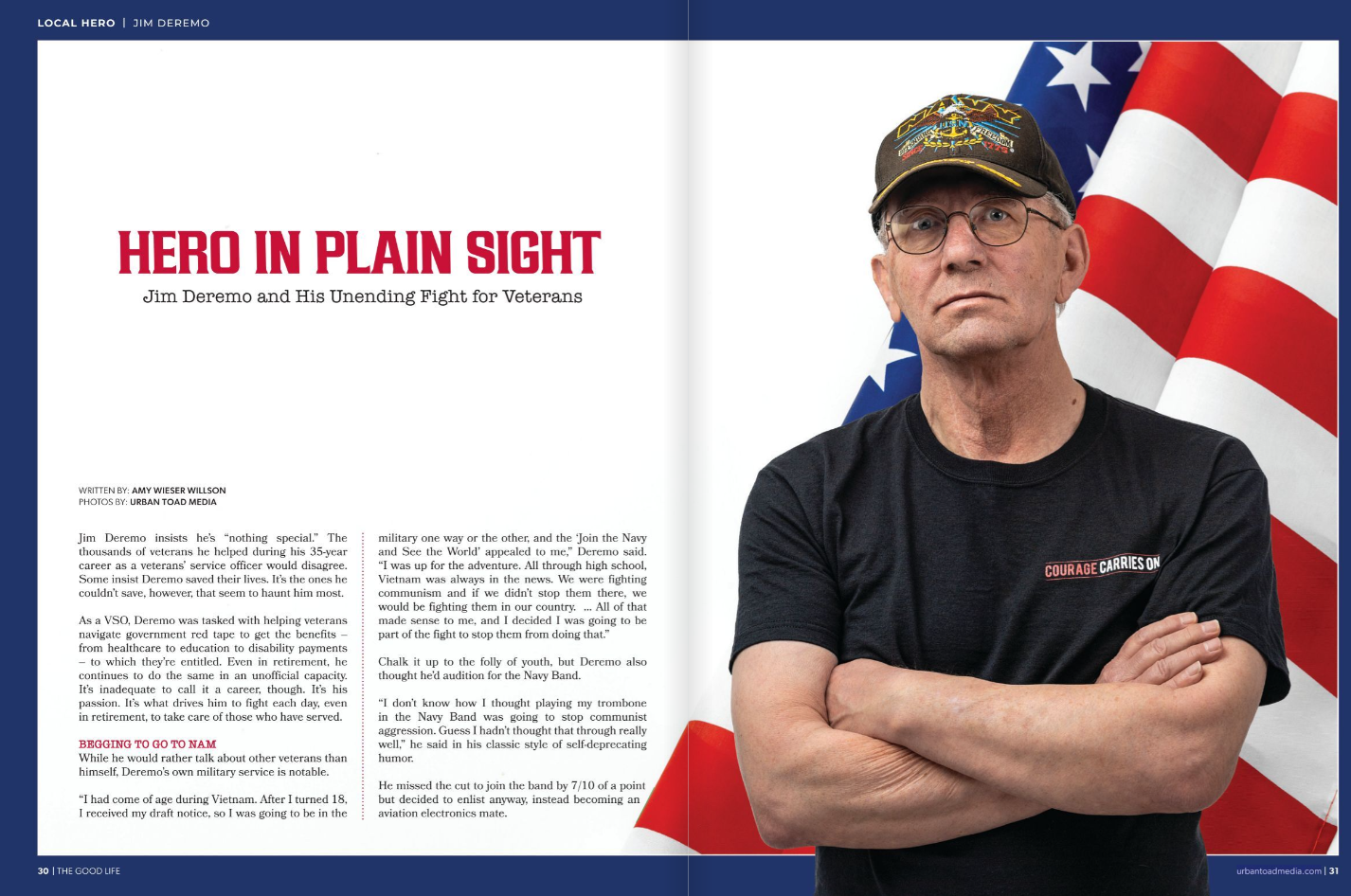

In our first Neon Loon Salute, I chose to feature Retired Lt. Col. Bernie Wagner. As a Valley City, North Dakota, native who also served an Army National Guard unit in that small town, I felt a connection to Bernie before we even began the interview. Although he passed away in 2015, I’m sharing this with the hopes that his legacy of service will continue to live on.

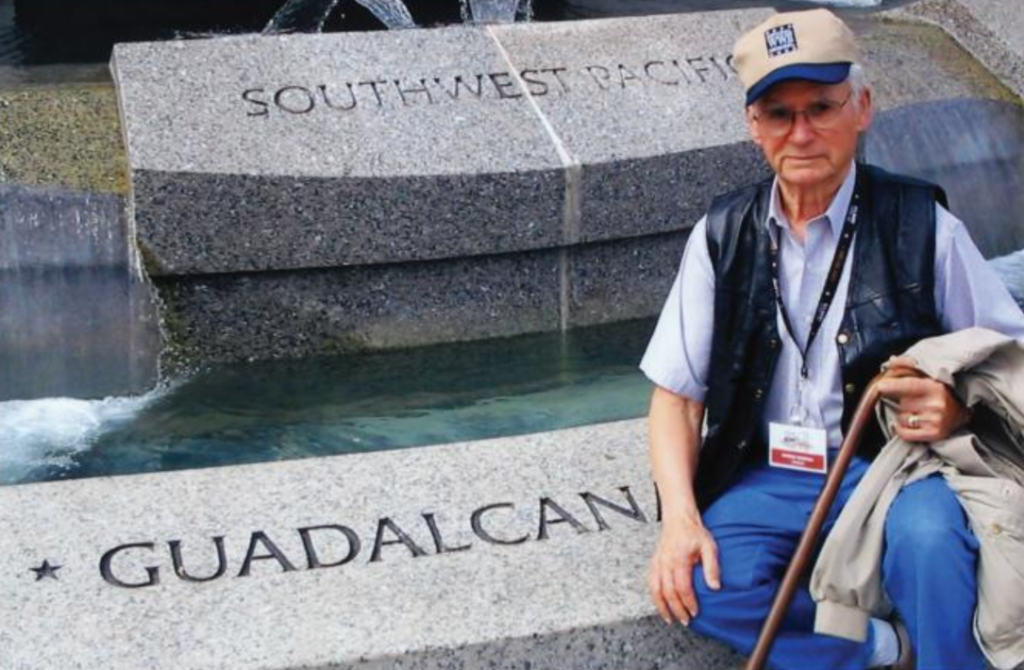

I still get chills when he describes his experiences in Guadalcanal during World War II, and I can’t help but smile at the rules he bent, first to get in and later to take care of his Soldiers. I will always salute you, Lt. Col. Wagner.

Bent, Not Broken

Veteran Won’t Let Rules, Injury Stand in the Way of Service

If there’s a theme that runs throughout Bernie Wagner’s illustrious military career and, indeed, his amazing life, it’s that he’s not afraid to break a few rules to get the job done and take care of his Soldiers.

Such was the case when he joined the N.D. National Guard at age 16, having lied about his age.

More recently, that mischievousness was seen when, against his daughter’s wishes, the 90-year-old Valley City resident “snuck out,” driving to Fargo with his wife, Mary, for an interview about his career.

It’s not easy to cover such a career in just a day, however, especially when Wagner’s legacy continues to bring together the Soldiers with whom he served decades ago.

‘GOTTA BE BORN IN 1919’

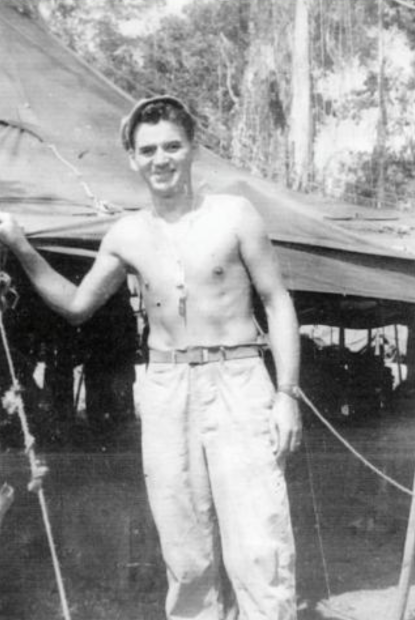

That career started in 1937, when the 16-year-old from Sanborn, N.D., went with a friend to the Valley City Armory. Wagner enjoyed the military-style marching his basketball coach, a North Dakota Guardsman, had them do at practice. Plus, the money was good: $1 a drill or $16 a quarter, which was equivalent to the cost of college tuition. So, he thought he’d sign up.

As he approached the battalion commander, the man asked gruffly, “What are you doing here?”

“I want to join the Guard,” Wagner replied.

“How old are you?” the commander shot back. “When were you born?”

“1921,” Wagner replied.

The commander looked at Wagner’s friend and said, “March him around the block and tell him he’s gotta be born in 1919.”

So, Wagner marched around the block and came back.

“I got down to the same office, same guy: ‘Whaddya want?’ he barked. I said, ‘I’d like to join the Guard.’ ‘When were you born?’ (he said). I said, ‘1919. ‘Sign right here,’ (he replied). So, I got in the Guard.”

Wagner was the newest infantryman with Company G of the 164th Infantry Regiment, joining them for drill in Valley City every Tuesday night. His work ethic was quickly noticed, and before long he was mortar sergeant and then platoon sergeant of the weapons platoon.

“We didn’t have weapons then; we just worked with a book,” he said.

MOBILIZING FOR THE WAR

In February 1941, the regiment was called up for Worl War II, but they still didn’t have weapons in the beginning. First, they reported to Camp Claiborne, La., where the Guardsmen experienced treatment like they had never before seen. A sign posted at the local swimming pool proclaimed, “No Soldiers or Dogs Allowed.” The sentiment seemed the same among townspeople.

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Wagner and his Soldiers were sent to guard the Golden Gate Bridge in San Franciso, Calif., since authorities feared an attack by paratroopers on the West Coast. They pulled shifts on guard with M1 rifles before retiring to the “cow palace” for sleep.

“We always joked that we each had our own stall,” Wagner said.

Leaving on Christmas day in an unheated, three-quarter-ton truck, Wagner’s platoon headed to Montana to guard the Bozeman Pass, through which equipment for the war effort was traveling. They were treated considerably better there, with highway patrolmen offering the Guardsmen rides and the town allowing Soldiers to watch movies at the theater for free. A resident who worked as a signal maintainer in the area got to be a friend of Wagner’s, taking him to mass on Sundays with the understanding that Wagner would “keep the guys away from their daughter.”

The man also gave Wagner a heads-up that the game warden might be paying him a visit based on reports that the Guardsmen were shooting deer in the area.

Always willing to bend the rules a bit to take care of his Soldiers, Wagner flatly denied the charges once the warden arrived. He insisted the men received fresh meat via train from Helena, Mont. He went on to explain that the attic, which held the butchered deer so it could cure, had been nailed shut before they arrived and was presumable empty, although the warden questioned the new-looking nails holding the door shut.

“I said, ‘How about having dinner with us,’ because he was there over the noon hour,” Wagner recalls of the conversation with the warden. “And he said, ‘What are you having?’ And I said, “Beef, roast beef.’ So, we had dinner and he got outside and he said, ‘That’s the best damn roast beef I’ve ever had.’ And it was deer. He had a job to do, and we didn’t waste anything.

SHIPPING OVERSEAS

In March 1942, after 13 months of stateside duty, Wagner and the rest of Company G headed to New Caledonia, a French colony in the South Pacific, which was a growing base for seizing control of the Soloman Islands. In “They Were Ready: The 164th Infantry in the Pacific War, 1942-1945,” author Terry L. Shoptaugh writes that the Guardsmen would, in general, recall New Caledonia as “a pleasant interlude in an otherwise grim war.”

Mary had the opportunity to visit Wagner while he was stationed in Bozeman, and it was there that he proposed marriage. Finding a time to get married would prove challenging, though.

“We had a really good crew,” Wagner said of his weapons platoon, one of four platoons in the company.

“We had a good company. I had the weapons platoon, and we were just an outstanding bunch of guys that stuck together,” he said. “I was their old cluck hen with the chicks.”

Wagner was loyal to that crew, and they to him. He soon became one of five in the company selected to attend Officer Candidate School.

“I wasn’t too hip about doing that, and anyway, we got alerted and the battalion commander, the last thing he said when we got into this truck was, ‘You stay and get commissioned, or you don’t come back.”

A half-dozen Soldiers from weapons platoon fought the move and begged for him to come back. The platoon sergeant knew little about weapons and Wagner had been training them for a while now. They took their concerns up to the commander.

“So, I quit OCS on New Caledonia and went back into combat with the guys as a staff sergeant,” Wagner said. “… When I think back, it was a good choice.”

FIRST TO FIGHT

They spent about six months protecting strategic interests in New Caledonia before deploying in October 1942 to Guadalcanal, where the First Marine Division had been battling fiercely against the Japanese since August for control of the unfinished Henderson Airfield.

Landing there was a confusing time for the men, who began marching not knowing where they were headed and soon became lost while being shelled. It was a day that the North Dakota boys would not soon forget. Even that morning’s breakfast remains a clear memory for Wagner.

“(It) was the only time I had baked beans at four in the morning, the day we left into Guadalcanal. … For breakfast, we had baked beans, and you remember that as a young guy.”

Once they connected with the Marines, they were briefed and told that the Japanese weren’t very good at shooting, “which wasn’t the truth,” Wagner said.

Wagner’s platoon members were good shots, too.

“We had good fighters,” he said. “Good Browning Automatic Rifle guys right up on the line. A BAR was a tough weapon. You had to keep it spotless otherwise it would jam.”

Before the month was over, those fighting skills would be tested. There were about 20,000 Japanese on the island – terrain with which they were familiar – fighting about 23,000 newly arrived Americans. The 164th would become the first U.S. Army unit to take offensive action against the Japanese during the war. Within a couple of weeks of arriving, Company G was sent to the southern part of the regiment’s area, where they spent four days in a fierce battle that left about 300 Japanese dead just in their vicinity, with bodies falling as close as 10 feet from their front line. The Soldiers held back the forces and maintained control of the airfield despite the barrage of Japanese willing to fight to the death.

“We knew that the Japs were there, so we set up the machine guns with the field of fire. … We had the men on the line, and I was back behind,” Wagner said. “And they thought they had eliminated the Japs … but this squad leader stuck his head up and he got hit. He was one of my best buddies.”

Wagner carried the man, Bill Carney, back from the line. On his way, he passed the mess sergeant who asked who Wagner was carrying. He had to deliver the awful news – “It was his brother.”

“That’s the bad thing. You get so close. I was probably closer to him than brothers were. You get so close in combat.”

Before leaving Guadalcanal, 150 North Dakota Soldiers would be killed in action or die from their wounds. Another 360 were wounded, Wagner among them.

PRESUMED DEAD

Wagner’s weapons platoon leader was killed and Sgt. Sam Noeske, from Jud, N.D., was wounded in battle on the island.

“I got knocked out at the same time, and the company commander asked if I would take them back, and I did,” Wagner said. He also helped carry back “the tallest guy in Emmons County,” who had been injured, and escorted two squad leaders who had “cracked up from the shelling that they’d got.”

After reaching the aid station, Wagner continued to insist he needed to go back to the line.

“The medica said, ‘You can’t go back. You can’t go back. You’ve got problems,’” Wagner recalled. “And I said, ‘I’ve got to go back.” So, he set me down and fed me aspirins every half an hour and pretty soon he looked at my eyes and said, ‘You can make it, but when you get back off of patrol, turning yourself in.’ I never did.”

As he approached the front again, a Marine from Tower City stared and said, “Bernie, I’ve got our helmet. I thought you got killed.”

The steel pot had a six- to eight-inch split across it, and Wagner credits it with saving his life. He lost it as he carried the other men back for help, though. When the Marine found it, he saw Wagner’s wallet with an ID tucked inside of the liner next to a rosary and presumed him to be dead.

Wagner quickly ensured his family had not been notified of his death.

With the loss of the rifle platoon leader, Wagner was given a field commission and the lieutenant’s rank.

“The company commander said, ‘You’re going to take over this platoon,’ and it was all goofed up with wounds … and it was a little tougher for me coming out of a weapons platoon to a rifle platoon. … I had to show them who was boss, and we got organized and went back.”

Wagner knew the men needed strong leadership, but he also knew they needed protection, which was something he had always provided his troops, whether it was covering for them sneaking into town for a beer or shotting game or preparing them for a series of drawn-out battles with the Japanese.

Wagner’s actions as he assumed command and “reorganized the platoon into fighting condition” earned him the Legion of Merit through Legionnaire (Combat) Conditions. A small red and white pin representative of the award still adorns his jacket.

MARRYING MARY

The men spent about five horrific months on Guadalcanal before being shipped to Fiji, which was a vacation in comparison. From there, they moved to Bougainville and Wagner was again sent back for Officer Candidate School since “I didn’t have a commission, but I had the bars.”

It was a new kind of challenge as he tried to become physically fit and resist the fights paratroopers would pick downtown to get the candidates to wash out.

“You were in good condition for combat, but not for push-ups and pull-ups,” he said.

Wagner connected with a dog trainer in the evenings, following the dogs around to get in shape. When the workout was done, he’d return to the PX and purchase a pint of ice cream for a dime. He shared the reward with the dogs.

Wagner had started the war as a “buck sergeant,” rose in rank to a first sergeant and then became a second lieutenant.

“That wasn’t a promotion for me, but it was a good thing, and I got to go back to the States, so we decided to get married. Mary had waited long enough.”

They wed in 1945 and then headed to Florida, where Wagner would teach jungle tactics.

“I’d gone to college and studied to be a teacher standard, so for our honeymoon, we got stationed at Camp Landing, Fla.”

WAGNER TODAY

Nearly seven decades later, onlookers can’t help but notice the love in their eyes as they look at each other. Wagner stressed the importance of family throughout his military career, and he encouraged his Soldiers to bring their families to camp during part of annual training each summer.

“It’s tough on families in the Guard, but we’d go to Guard Camp and if they could make it, we’d work it out some way to get them up there for extra duty,” Wagner said of the families. “And what the colonels didn’t know as all right. We didn’t tell them everything.”

In 1950, the 164th got called up again, this time for the Korean War. Wagner was pulled early from a military school in Fort Bliss, Texas, and headed home.

He got the promotion he was going to school for despite leaving early, and by Jan. 16, 1951, was on his way to Fort Rucker, Ala., with Company G. While there, however, he was hospitalized as a result of the injuries he sustained during World War II. Despite that, he moved his family back home at the end of their stay at Rucker and reported to the West Coast to prepare to ship overseas. It was there that they pulled his medical records and told him no. Instead of deploying with his men, he spent 20 months guarding a Northern Pacific railway stateside. Despite his loyalty to his men, he knew the danger of war and the importance of surviving to return home and provide for Mary and their two young children, Pat and Chuck. He had just started farming, as well.

Five years later, a major organizational change took place in the Guard, converting all units to engineers. Valley City’s 164th became the 141st Engineer Combat Battalion, and Wagner would serve as the new headquarters’ first training officer, and later its executive officer and battalion commander. He eventually retired as the state maintenance officer for the N.D. Guard. After all of these years, a “141” license plate still adorns his car. He still carries a 141st matchbook in his pocket, too.

“We always promoted the 141 … you carried these … and if somebody flashed this to you, you had to have this,” Wagner said of the matches. “If you flashed it and the guy had one, well then the one who flashed had to buy a drink, but if he didn’t have one, he had to buy for the whole group.”

His ties to both units remain strong, and he continues to organize annual reunions for the 164th Infantry Regiment as well as biennial reunions for Company G members. Pat serves as the secretary for the 164th Infantry Association of the United States of America and helps prepare the invitations. Mary stuffs the envelopes. Wagner’s son, Chuck, followed in his dad’s footsteps and served as Maj. Gen. Mike Haugen’s chief of staff before retiring from the Guard as a colonel – one step higher than his father’s retired rank.

“The military was a good life for us,” Wanger said. “It kept us going.”

Nearly 75 years after enlisting in the N.D. Guard, it would be hard not to argue that Wagner, in return, helped keep the Guard going and continues to service his fellow Soldiers and his country in many ways.

This story was originally published in the North Dakota Guardian in September 2011.

Neon Loon Salutes showcases the stories of men and women who have served in the United States military. As a veteran-owned business, Neon Loon Communications’ team feels passionately about preserving the heroics, both big and small, of those who have fought to keep our nation free. Their stories give a personal look at what it takes to serve during war and peace. If you or someone you love is a veteran interested in telling their story, please email amy@neonloon.com.