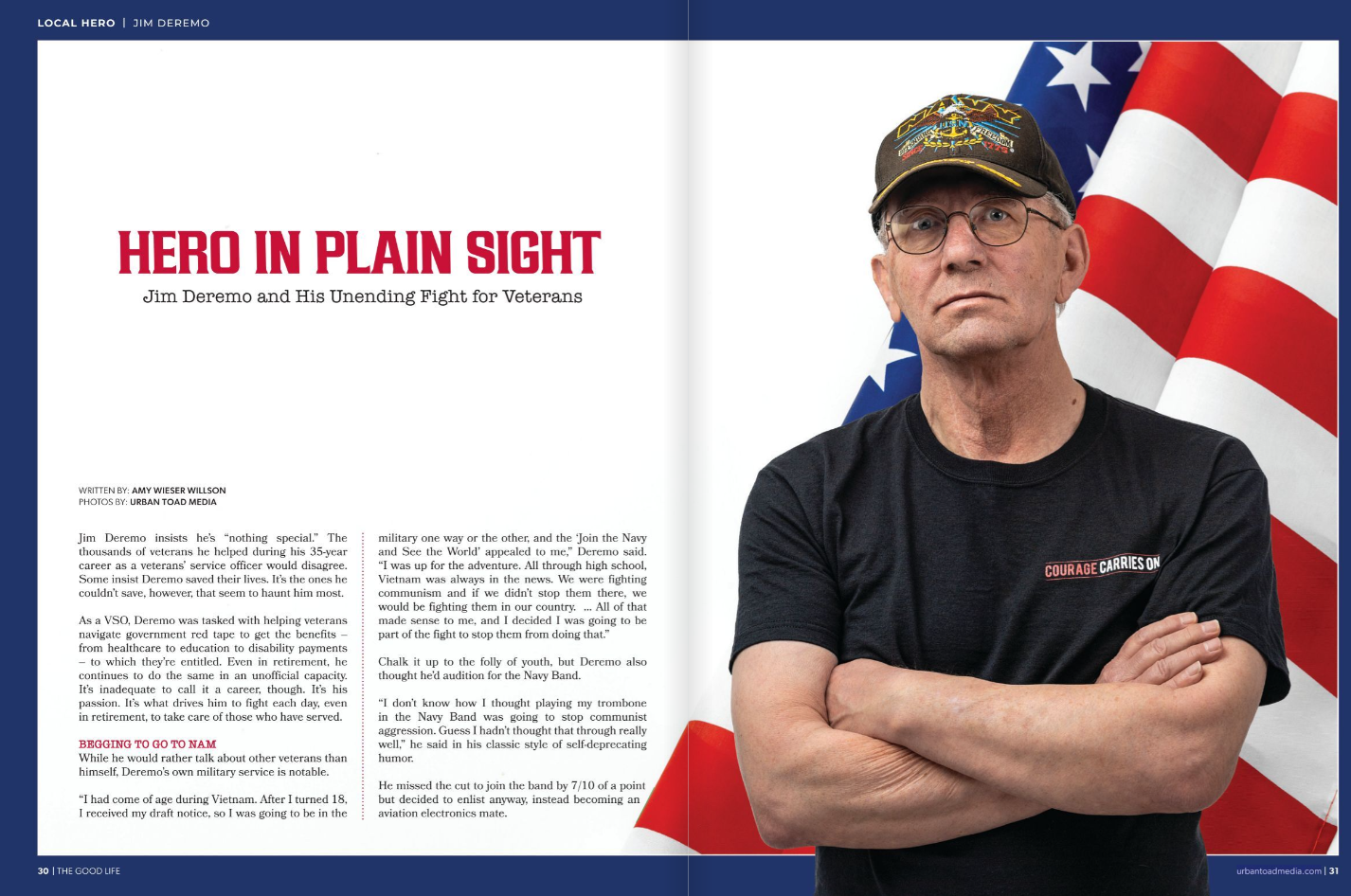

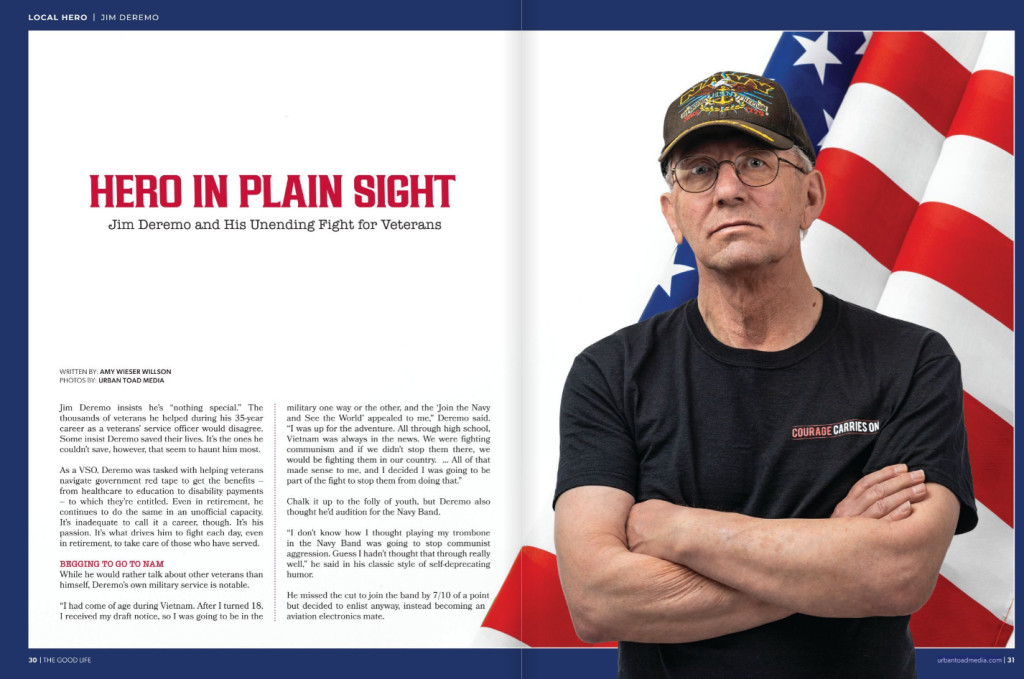

Hero in Plain Sight: Jim Deremo and His Unending Fight for Veterans

Jim Deremo insists he’s “nothing special.” The thousands of veterans he helped during his 35-year career as a veterans’ service officer would disagree. Some insist Deremo saved their lives. It’s the ones he couldn’t save, however, that seem to haunt him most.

As a VSO, Deremo was tasked with helping veterans navigate government red tape to get the benefits – from healthcare to education to disability payments – to which they’re entitled. Even in retirement, he continues to do the same in an unofficial capacity. It’s inadequate to call it a career, though. It’s his passion. It’s what drives him to fight each day, even in retirement, to take care of those who have served.

BEGGING TO GO TO NAM

While he would rather talk about other veterans than himself, Deremo’s own military service is notable.

“I had come of age during Vietnam. After I turned 18, I received my draft notice, so I was going to be in the military one way or the other, and the ‘Join the Navy and See the World’ appealed to me,” Deremo said. “I was up for the adventure. All through high school, Vietnam was always in the news. We were fighting communism and if we didn’t stop them there, we would be fighting them in our country. … All of that made sense to me, and I decided I was going to be part of the fight to stop them from doing that.”

Chalk it up to the folly of youth, but Deremo also thought he’d audition for the Navy Band.

“I don’t know how I thought playing my trombone in the Navy Band was going to stop communist aggression. Guess I hadn’t thought that through really well,” he said in his classic style of self-deprecating humor.

He missed the cut to join the band by 7/10 of a point but decided to enlist anyway, instead becoming an aviation electronics mate.

When he finished training, he completed his “dream sheet” of where he wanted to be assigned.

“I put down Vietnam as my first choice, so, of course, the Navy sent me to Naval Air Station Miramar, near San Diego,” Deremo said. “After about a year at Miramar, I got to fill out another wish list and, of course, I put Vietnam as my No. 1 choice. So, they sent me to a school at NAS Lemoore, California.”

After completing the next round of training, he again listed Vietnam as his first choice. This time he was assigned to the USS Constellation, an aircraft carrier, and soon started his long-awaited trip to Vietnam.

They positioned just off Vietnam’s coast and supported ground troops by bombing enemy positions, supplies and supply routes. They also shot down enemy aircraft, all while battling typhoons and jet fuel fires next to jets loaded with bombs and missiles.

After his December 1973 discharge from the Navy, Deremo stayed with his parents in Arkansas City, Kansas. College was up next for him, so it made sense to transition at home.

“I kinda missed the hippie movement, so I thought I’d let my hair and beard grow,” Deremo said. “Me and my dad were sitting at the table one night talking, and he said, ‘You ought to shave that beard off. What the hell’s with that?’”

Always ready with a clever comeback, Deremo declared, “Good enough for Jesus, good enough for me!”

His dad quickly responded, “But Jesus didn’t live in my house!”

So, off Deremo went to Dakota State College in South Dakota for a teaching degree.

SEEING THE NEED

While there, he was elected president of the Collegiate Vets. That connected him with more veterans as he attended state conventions for the VFW, DAV and American Legion. It also led him to a work-study program on campus, where he ran the veterans’ office, filed paperwork, and spent time “fighting with the VA.”

After college, he was offered a job as a field officer working with veterans, so he figured he’d take it until he got a teaching job. Now, at age 73, Deremo has yet to work as a teacher. That doesn’t mean he hasn’t impacted countless lives, though.

He got a glimpse early on of the struggles veterans face. One night, while he was still in the Navy, a friend in the barracks called out to Deremo.

“He was standing there by his rack. He had slit his wrists, blood all over. I got some towels, wrapped his wrists in them and drove him to the base dispensary. I was scared he was going to bleed out and die before I got him there, but he didn’t.”

At the dispensary, a corpsman patched the wounds and said Deremo’s friend “wasn’t serious about committing suicide because he slit his wrists the wrong way.”

At the time, Deremo had no idea that his life would be spent helping more men and women just like that friend.

FIGHTING FOR VETERANS

Deremo remembers many of those veterans, who have served in the Mexican Border War and World War I all the way to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

There’s Harlan, the Marine who had shrapnel damage in his hand and had little feeling left after the nerves had been cut. The injury resulted in him running a saw through his hand without even feeling it. The VA Board of Appeals denied benefits since it wasn’t a direct war injury, even though that’s what precipitated it. Harlan became the first case Deremo would fight in the new Court of Veterans Appeals, where he was authorized to practice before the court even though he had no legal training. Despite everything stacked against them, Deremo won the case. He later fought for Harlan again when he was going to be fired as a direct result of the injury, a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

There’s Jerry, who was drafted as a dentist in the Vietnam War. With little dentistry work to do, Jerry helped elsewhere. At one point, he performed a tracheotomy in the field with a pen. He got shot in the hand in another incident, which prevented him from being able to return to the dental clinic he had established just in time to get drafted. The VA denied Jerry benefits because he was a dentist, which they considered a safe role. Deremo changed their minds.

There’s Russ, who had three Purple Heart medals and was diagnosed with MS. That led to a nursing home stay and then a brain tumor Deremo is convinced resulted from Agent Orange exposure. Deremo fought to reverse the VA’s decision to deny nursing home care. After Russ died, Deremo worked to ensure his widow and four minor children received the benefits due to them, too.

“When you can change somebody’s life doing this, that’s the payday.”

But there’s also the Iraq War veteran who Deremo received a call on and fought to get into inpatient PTSD treatment. While there, however, he received a weekend pass and took his life at a hotel.

And there’s Dan Olson, a two-time Iraq War veteran who biked across North Dakota in 2010 and 2011 to raise awareness of PTSD and in memory of losing his friend and fellow veteran, Joe Biel, to suicide. Deremo coordinated the trip with Olson to raise money for veterans, and he followed Olson from one end of the state to the other with the support vehicle over the six-day ride. Olson disappeared in October 2021 and has never been found.

Despite the awards and gratitude Deremo has received over the years – including from people he doesn’t remember who have approached him and thanked him for saving their lives – he carries the weight of those he couldn’t save with him.

It’s not just war veterans that he’s fought for, either, and it’s about more than securing benefits. It’s about truly helping. A young soldier, one of the many military sexual trauma victims, shared his story with Deremo.

“I told him, if you have PTSD, you’re going to have to deal with it, rather now or later, and it’s going to be easier to deal with it now.”

Despite all the bad experiences Deremo witnessed, he’s incredibly proud of his three daughters, two of whom enlisted in the military, as well.

BRINGING THE FIGHT HOME

It’s not just his fellow Vietnam veterans who have experienced the effects of Agent Orange. Deremo himself has faced an array of health issues, including being diagnosed in 2020 with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which the VA considers a “presumptive disease” resulting from Agent Orange exposure. That presumption, however, wasn’t in place until the 1990s. It took until 2019 for the Blue Water Navy Veterans Act to pass – something Deremo fought tirelessly for – which acknowledged that sailors on ships within 12 miles off the coast of Vietnam also were impacted.

“We fought for years and years and years just to prove that we were exposed,” Deremo said.

He still fights other illnesses and the residual effects of the cancer, but he considers himself lucky.

His brother Randy served as a Marine in Vietnam. He died at 68, in 2018, because of Agent Orange.

When asked what the good life means to him, Deremo’s response echoed the challenges he’s faced: “Being alive is kinda a good thing.”

“Seriously, every day is a blessing. I should have been dead so many times.”

Each day alive also advances Deremo’s mission to save others.

“It was a fun career, I gotta say, but they wore me down,” Deremo said of choosing to retire. “I was getting tired of the stupid shit (the VA) did 20 years ago, and they’re still doing it.”

And Deremo is still fighting it.

This story originally appeared in the May-June 2024 issue of The Good Life magazine.